#Didyouknow that a very active art scene of prints existed in 19th century Bengal in North Calcutta (now Kolkata) which was available for everyone? We are talking about the ‘Battala prints’ which were made in different forms on reasonably priced paper. There were pamphlets, posters, illustrations for books, ephemera, artworks, advertisements for the local jatra, (a form of theatre) enjoyed by all folk. This artform made as a woodcut or metal-cut print which evolved from the Kalighat ‘pat’ was a great leveller and seems to have had no boundaries. Innovation was very well accepted. Let us find out more about this artform and take a nostalgic journey!

What is a woodcut?

According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that the artist cuts away carry no ink, while characters or images at surface level carry the ink to produce the print. The block is cut along the wood grain (unlike wood engraving, where the block is cut in the end-grain). The surface is covered with ink by rolling over the surface with an ink-covered roller (brayer), leaving ink upon the flat surface but not in the non-printing areas. Since its origins in China, the practice of woodcut has spread around the world from Europe to other parts of Asia, and to Latin America. Woodcut, which appeared in the 8th century in the East and in the early 15th century in the West, is the earliest known relief-printing method. Although woodcuts are generally conceived in bold lines, or large areas, tonal variations can be achieved with textures, a variety of marks made with gouges, chisels, or knives. In contemporary woodcuts many other methods, such as scraping, scratching, and hammering, are also used to create interesting textures. The standard procedure for making a woodcut with two or more colours is to cut a separate block for each colour. If the colour areas are distinctly separated and the block is large, one block can be used for more than one colour. All blocks must be the same size to assure that in the finished print the colours will appear in their proper relation to one another, that is, properly registered”

Journey of the Woodcuts of Bengal

Woodcut printing happened at Bat-tala which literally means the underneath area (tala) of a banyan tree (bat or ‘baut’) or the environs of a banyan grove. The area probably had a number of trees at that point of time. Now they are not found. The art of printing took place in the lanes of this area in North Kolkata, in fact it is the birthplace of the Bengali printing presses in the early 19th century. The woodcutters lived around the Chitpur and Shovabazaar areas. Stone and burnt clay were also used in printing. Battala was an important centre for woodcuts. The area was a melting pot for cultural activities which included jatra; music programmes, also printing on various topics including religion, mythology, current affairs, mystery and suspense, books on history, biographic plays, even erotica, printing almanacs and calendars, artists workshops and markets as well.

Woodblock printing on fabrics has been in India for centuries which has even been traced to Egypt in the 6th and 7th centuries. Woodblock printing on paper came much later. Battala had many printing presses in the 19th century, around 46 run by Indians. In 1857, 322 titles in Bengali were produced from these presses, among which there were 19 almanacs. In fact, Biswanath Deb was the first person to set up a press in 1818 and published the first title. The Battala prints could not last for a very long time because of new technology called lithography. Very few of these prints have survived because of humidity and also the quality of paper used was not very good in order to keep its cost less, so many people could buy the same. The Battala area became known for the prints in the early 19th Century. They made their first appearance in the 1820s as book illustrations; by the mid-nineteenth century, printmakers started printing the smaller prints, which often represented Kalighat paintings.

Battala woodcut prints were made by people from all castes. The products covered a plethora of subjects. The books were carried by hawkers to the smaller towns and villages. It is mentionable that other than illustrating books the Battala artists made large letters for handbills and posters, designed for advertisements and labels as well.

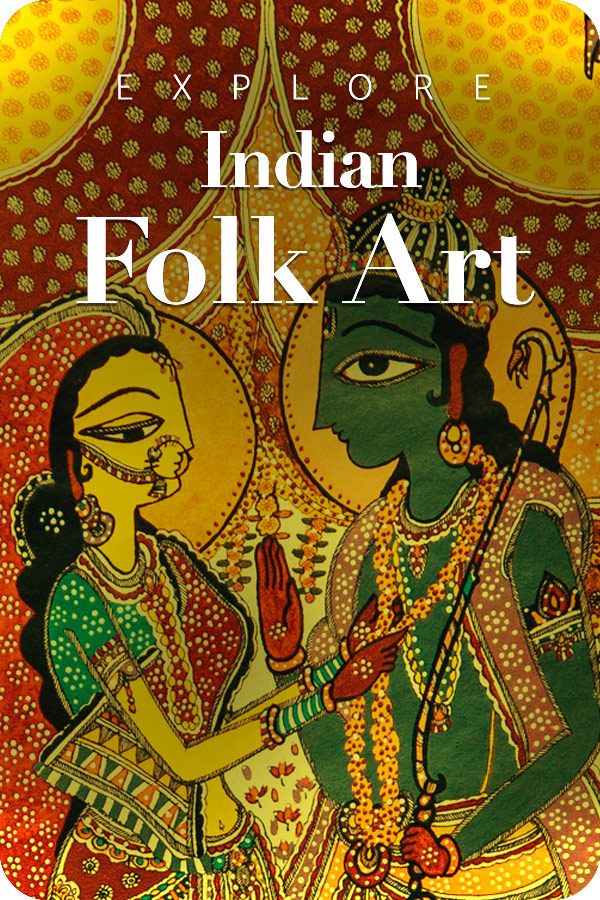

The Calcutta woodcuts were quite similar to the Kalighat ‘pat’ artworks. The Kalighat ‘pat’ was a reflection of the times and the social mode which existed then. Battala prints were a variation which flourished most around 1850s and continued to the ’60s and ‘70s. They were cheaper than the Kalighat ‘pat’ made by the patuas. Some were imitations of the ‘pat’. The subjects included Hara-Parvati, Annapurna, Gaur Chaitanya and Krishna-leela. Krishna-leela had Rajasthani influence. Other than these the love story Bidyasunder was in vogue. The Battala artworks had the artist’s name on them and there was a focus on signature styles and individuality. There were many artists; Gobindochandra Rai and Hiralal Karmakar to mention just two. The Kalighat ‘pat’ declined by 1930, while the Battala woodcuts declined by the 1890s. As mentioned, demand for the prints began to decline with the introduction of colour lithography printing. However, for few decades Battala had book engravers for illustration and poster-making for the jatras.

Some glimpses of the artworks

Let us check out some prints preserved in different places and appreciate these works which were quaint, beautiful, arty and quirky as well. The first artwork depicts Goddess Durga who is slaying Mahishasura as he is emerging in his human form. Goddess Durga is flanked by Lakshmi and Ganesha on the left and by Sarasvati and Kartikeya on the right. This artwork depicts Durga as she is worshipped during the Durga Puja festival in Bengal.

The artwork titled as “Untitled” looks not so easy to decipher. It is coloured and shows a Ravana like figure probably fighting with a Hanuman like figure from the Indian epic Ramayana. It could have been probably used as a poster for a jatra.

The Met Museum says about the next artwork in two columns – “This double-image is printed from two metal plates on a single sheet of paper is one of the pioneering images of Calcutta print-making. They are referred to as Battala prints, named after Battala, a locality in the Hooghly district of Kolkata, where many local presses had been established in the early to mid-19th century. The print engravers worked both on metal sheets and woodblocks. The print on the left depicts the goddess Kali standing on the prone figure of Shiva, wielding a sacrificial blade in a raised hand while holding by a tuft of hair the severed head of her victim in her lower hand. Her expression, with wide eyes, blood-stained mouth and protruding tongue—intended to instill terror in the disbeliever—is a source of comfort to her devotees.

The second print (right) depicts the goddess Jagadhatri, a form of the Hindu goddess Durga, in a near identical setting of a Europeanized columned pavilion. Like Kali, to whom she is related, Jagadhatri is also honoured lavishly in an annual puja held in the Hooghly district of Kolkata in the month of Kartik (mid-November). A third eye in her forehead and a snake rising above her right shoulder signal her allegiance to Shiva. The goddess sits upon a lotus-cushion, poised majestically upon her lion vehicle (vahana), wielding her divine weapons. She is flanked by two female guards and at her feet kneel a worshipful couple. Both goddesses are framed by a Victorian cusped arch supported on slender openwork pillars with Ionic capitals, all evocative of the cast-iron architectural décor that was such a feature of British Calcutta”.

The ‘Reclining lady with a man’ image very much resembles a Kalighat painting. It depicts a Bengali Nawab with his bibi, a upper-class lady who is in a reclining posture.

The image from Wellcome Collection shows Sri Chaitanya and Nityananda standing under a canopy and flanked by Advaita Acharya and Srivasa Thakura, made by artist Govind Chander Rai.

A very unique picture of Lord Krishna steering a mayurpankhi (peacock-headed boat) with gopis, the cowherd maidens and an old lady, Radha may be seated in the enclosure.

Though this art is more or less obsolete and few people know of it, it remains an art which reached out to everyone and had a democratic appeal. It has left an indelible mark in the art history of Bengal and can’t be forgotten. Museums and private collectors are still preserving extant examples of this unique artform from 19th century.

References –

Paul, Ashit, ed. Woodcut Prints of Nineteenth Century Calcutta. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1983.

https://www.immersivetrails.com/post/battala-and-before-the-development-and-demise-of-the-woodcut-prints-of-calcutta (accessed 7th October 2022)

https://medium.com/the-calcutta-blog/battala-and-before-94759bab0d3e(accessed 20.10.2022)

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battala_Woodcut_Prints(accessed20.10.2022)

Images used are from Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome images (Public domain) and Flickr.